Out of the rough revisited… A tale of two golf courses (at Stowe)

Sarah Rutherford, of Bucks Gardens Trust

This is a tale of two golf courses and what exemplary restoration can be achieved in a great landscape garden with the generosity of an anonymous benefactor. It is a good news story, one which was unimaginable some twenty years ago when as an aspiring conservation professional I sent for a copy of In the Rough. Longstanding members will recall that this was not some investigation into the seamier side of urban life by Ian Sinclair, but a hard-hitting report commissioned by The GHS, The Georgian Group, and then newly-formed Association of Gardens Trusts to examine the effect of golf courses in landscape parks.

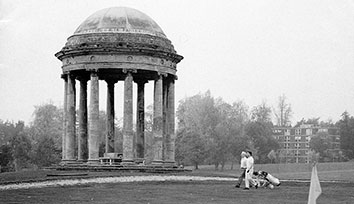

In the Rough set out the basic incompatibility of landscape parks and golf courses as they were being designed at the time, and tried to suggest solutions. The front cover was illustrated by one of the more notorious examples of a golf course in a landscape garden, the Stowe School golf course in Lord Cobham’s seminal Home Park at Stowe, arguably the greatest landscape garden of the lot. The image showed one of the earliest and most influential garden rotundas (Vanbrugh, c1721) juxtaposed with the paraphernalia of a golf course. The National Trust bizarrely used a very similar image in their latest magazine to illustrate Stowe’s place as a favourite garden; of all the images of the beautifully restored Stowe they might have picked!

Golf quickly became a key part of school life after the core of the Stowe estate was rescued in 1922 for use as a great new public school in rural north Bucks, in a pioneering conversion by the architect of Portmeirion, Clough Williams-Ellis. Outdoor activities were and remain a key part of the school ethos. The school golf course was set up around the palatial mansion. The Stoic, the school’s magazine, in 1924 asked, ‘What happens to golf balls played into the Headmaster’s garden [on the south front of the mansion]? The peacocks who eat the bulbs there daily are suspected of having some guilty knowledge on this matter. What happens to the player is of course a different question.’ The 9-hole course now occupies the Home Park and the great south vista and remains part of the school facilities.

Plan showing how the 1st and 2nd fairways of the golf course run across the bottom of the main vista from the mansion to the Octagon Lake, and covers the Western Gardens

The Stowe golf course illustrates well the key difficulties of constructing a golf course in a landscape park or garden without damaging the landscape character, which have of course been rehearsed over the years by various Conservation Officers in this very GHS organ. These chiefly relate to the remodelling of the ground for greens, tees, bunkers and hazards, planting of alien vegetation in lines to define fairways, and the alien appearance of golfing features, equipment and turf management regimes. When the pioneering Stowe Framework Conservation Plan was drawn up by Inskip and Jenkins for the National Trust and Stowe School in 1999 it highlighted the damage done by the golf course to one of the earliest parts of the landscape garden and firmly called for its removal at the earliest opportunity (which seemed unlikely ever to happen).

The dilemma was, how to do this? The school did not wish to give up its golf facility, with a small private club attached, but was aware of the incongruous nature of a golf course in this uber-sensitive position for the garden and mansion. The National Trust were also keen to see it go from here but had no means of facilitating this. The solution came recently in the form of an anonymous benefactor who, keenly aware of the issues, philanthropically offered to pay for the re-siting of the golf course in a less sensitive area of the Grade I registered Stowe landscape, if one could be found. This almost unimaginable scenario was applauded by both the National Trust and Stowe School, who jointly set about locating a suitable site. This turned out to be centred on a convenient piece of relict agricultural land around Lamport village which Lord Cobham and Earl Temple had never been able to acquire for their park. Instead they had turned their backs upon it and screened both village and fields from their Arcadian landscape garden. How convenient!

Howard’s map of 1843, showing Lamport village, middle, with the Bourbon Tower above, encircled by 8 oak clumps planted by the French Royal family when its exiled members visited in 1808

The land chosen is owned by both bodies and wraps around the earthwork remains of Lamport village and two surviving, privately-owned, village houses (largely rebuilt). This core area links the Deer Park to the north, containing Lord Cobham and Gibbs’s Bourbon Tower (c1740) with Bridgeman’s 1720s Bycell Riding in agricultural land to the south next to Gibbs’s Stowe Castle (c1740). A landscape analysis highlighted the significances of the various areas and the restoration required to reinstate the historic landscape. This formed the basis for the next stage which was to set out a 9-hole layout taking into account all the constraints, particularly the grade I registered landscape, archaeological features, the concerns of other owners, public rights of way and wildlife. Here was a marvellous opportunity for an exemplar golf course design, minimizing the visual and physical effects on the historic environment while creating a testing golf course which would suit learners and experienced golfers alike, and restoring much of the historic landscape in which it was to sit.

The genial gentlemen of the Sports Turf Research Institute (STRI) who were commissioned to design the course initially were pretty relaxed about fitting the golf course into the area chosen, thinking that it was generous for the needs of a 9-hole course. By the time they had been apprised of all these constraints they were scratching their head, it was quite a test to fit it in and still provide a good playing facility. They had not dealt with golf in historic parks, nor their demanding champions, before, but quickly got the message and responded with aplomb.

The ancient ‘Fairy Oak’ another ‘heritage asset’ on the new golf course, named after a Mr Fary. The oak stands on the edge of Fary’s Close – he was a tenant on the 1633 rent roll

But what about access to the course, car parking, and where to site the club house, at present essentially a garden shed next to the remains of the pyramid near the East Boycott Pavilion? Could the club house be picked up with a crane and dropped onto the new course, a mile or so away? Would a new one have to be built in the C18 landscape and if so where and how could its visual impact be minimised? Conveniently the north end of the chosen site bordered the school’s playing fields and changing rooms, already largely screened from the C18 landscape and containing car parking. A new club house could be sited here with the first tee adjacent and the last hole nearby, well screened from the C18 landscape and with access, services and parking established.

Planning permission was applied for with all the necessary information to support the siting and layout of the course, and was granted in April 2012. The GHS, which had been consulted at an early stage of the design, warmly applauded this proposal and endorsed it as an exemplary approach to such a case. English Heritage had concerns about ensuring that the old golf course would be shut and the Home Park and its surrounding wildernesses restored, but the National Trust was delighted to agree to take on the area, and undertake the restoration of the final piece in the jigsaw of Stowe Landscape Garden on the basis of an updated conservation management plan.

So what next? Work on the new golf course and the restoration of its historic environment will take place in 2014, and it has to be allowed to mature for a year before it can be played on. This takes us to the autumn of 2015 for the opening of the new course and closing of the old one, with the restoration of the Home Park following on from this. We can only be grateful for anonymous benefactors, without whom the renaissance of many examples of Britain’s greatest contribution to the visual arts would not be possible.

A version of this article appeared in The Bucks Gardener 33, Spring 2013, newsletter of the Bucks Gardens Trust.