Amber Hare writes:

In a period perhaps best characterized by social and economic pandemonium, one must not only prepare for the impending havoc, but also take a moment to savor that delightful quiet preceding any storm worth a salt. With this in mind, there is no time like the present to dip one’s toes in the pond of conjecture…

This dabble with visualization begins in the early-20th century. Imagine you’re a shrewd magnate looking to spruce up your yard. Colonel George and Nelle Fabyan deemed a Japanese Garden the idyllic compliment to their Riverbank estate, in Geneva, near Chicago, which was already nothing less sumptuous. The couple hired landscape designer Taro Otsuka to construct the site sometime between 1910 and 1913 and upon completion, Susumu Kobayashi for maintenance and periodic cultivation. As an emotive result of personal expression applied to one’s environment, gardens serve as tribute to the natural world and the human condition. An internationally celebrated art, gardens are cultural reflections of the individual gardener and their community. Spectacular personal touches, paired with the landscape’s precision, make the Fabyan’s Japanese Garden marvelously captivating.

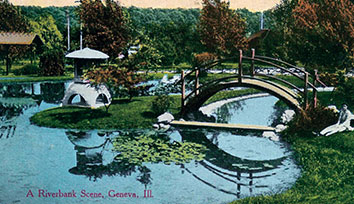

An early overview of the garden with Moon Bridge (courtesy of PPFV)

After centuries of evolution, Japanese Gardens are an amalgamation of social and religious ideologies. The influence of Zen theory transformed flowers into signs of frivolity. Subsequently, Japanese Garden flora is now typified by a quixotic interplay amongst immeasurable shades of green. Conifers, symbolizing self-discipline and eternity, have since reined champion as the choicest specimens. The contemplative journey is intended to inspire serenity and humility through a heady fusion of natural and man-made elements. The symbolic significance of any given feature is cumulative and thus, not disparate from that of the garden as a whole. Thoughtful compositional intricacies make Japanese Gardens an ideal setting to seek intellectual and spiritual sanctuary.

One must pass through the Gateway to Heaven or Torii gate, traditionally used to demarcate a Shinto shrine, to enter the Fabyans’ garden. An appreciation of the landscape is realized by the garden path composed of various mediums to strategically moderate one’s gaze and pace. Since the garden is not passively experienced, interpretation occurs on a personal level. Upon embarking, one meets the Waiting Bench Chamber. A sanctum of calm acceptance and understanding of oneself and nature, the Chamber employs both a circular and a square window to restrict vistas and manipulate one’s perspective.

The expedition continues on to the Buddhist center of the universe, Mount Sumeru. Its summit and the wooden bridge crowning it are dauntingly steep, an effort taxing to mind and body that dramatically slows one’s passage. These ingredients emphasize the panorama granted upon surmounting the peak. Moreover, mountains, among other natural structures, were traditionally viewed as the residence of celestials.

One must forge a meandering stream, an existential nod to the stages of life, to reach the next destination. For just as human existence can be categorized by birth, maturity and death; water, too, transforms from torrential waves to placid silence. Once across, one has reached the Tea House situated in the most hallowed area of the garden, whose layout is intended to represent a piece of (Japanese) calligraphy. Launched in Japan during the 9th century, by Chinese Buddhist monks, the custom of drinking tea was a celebration of spiritual and social tradition. This rite animated standards of decorum, occurring in the chashitsu, a room utilized for the service alone.

The ‘Moon Viewing Area’ of the Tea House (courtesy of PPFV)

The Fabyans’ Tea House is ornamented with a droll little porch with a big name; the ‘Moon Viewing Area’ forms a perch from which to note phases of the moon. Because it does not contain a tea-preparation kitchen or separate entrances for visitors and the Tea Master, the building is not entirely accurate in terms of conventional guidelines. However, the structural discrepancies could be a result of how the space was used, as accounts from the era indicate that the Fabyans’ Tea House was primarily used for entertaining.

From here, one next encounters the Moon Bridge, known as such due to its reflection in the water below creating a ‘full moon’. Representing eternity through its intrinsically globular shape, navigating the incline requires a steely discipline. The proverbial path to enlightenment is not all roses and this venture symbolizes the arduous route between mortal and divine worlds. The bridge also draws attention to the elixir of existence: water.

Historic postcard showing the Moon Bridge and lantern like ‘Mount Fuji’ (courtesy of PPFV)

Given that Japan is an island, water is an essential garden element and the Fabyans’ garden is home to a relatively large crescent shaped pond. Portraying the surroundings is a central mandate to Japanese Gardens and thus, the Moon Bridge is accessorized with a lantern-like version of Mount Fuji. The peak’s eloquent formation denotes halcyon days and is, therefore, an allegorical badge of prosperity.

Emerging from this foray, one is a token wiser, and infinitely more aware of nature’s genius. Having survived a fling down the gauntlet of consciousness with one of the 19th-century’s most bewitching couples, one can now unequivocally state that the Fabyan Japanese Garden is an intoxicating study of basic truths. The quintessence of elegance, this is a space where imagination can flourish.

Fabyan’s Moon Bridge after recent snowfall (photo by Kelly Nowak)

Fabyan Japanese Gardens are open 3 May to 15 October, on Sunday 1 to 4:30pm, And Wednesday 1 to 4pm (from June), at other times by appointment. Admission by donation: $1! The Fabyan Villa Museum and Japanese Garden are located 42 miles west of Chicago, in Geneva part of the Fabyan Forest Preserve, on Route 31 (1511 Batavia Avenue), 1¼ miles south of downtown Geneva. IL 60134. The main entrance is on the east side of Route 31, just north of Fabyan Parkway.