Christopher Thacker was the founder editor of our journal Garden History, a great garden historian, and a good and kind friend.

Min Wood has written this appreciation which appears in our upcoming journal.

In Memoriam:

Christopher John CharlesThacker (1931–2018)

Christopher Thacker, who died on 27 September 2018 at the age of eighty-seven, was one of those who put intellectual backbone into the study of garden history. Born at Bishops Cleve, Gloucestershire, his family set up home in Southampton, Hampshire. His father was a tax collector who, perhaps to bring light relief from his occupation, amassed a large collection of Punch magazines. From an early age, Thacker junior was captivated by the cartoons and the satirical content of these, as far as he could then understand them.

As the German bombs began to fall on Southampton in 1940, Thacker was removed to Godalming, Surrey, into the care of a strict Quaker, the headmaster of a school which he also attended. He was encouraged to read the Bible and avoid any light reading. ‘There is no need for any other book,’ his headmaster told him, ‘it contains all the stories which may be found elsewhere. Tell me Christopher of anything in a library which contains any others.’ ‘Yes,’ said the ever-cheerful Thacker, ‘Punch’. That devotion to humour sustained Thacker through his long life both as a tool for persuasion and an antidote to melancholy.

After Portsmouth Grammar School, which fostered his love of music and acting, Thacker did his national service in the RAF, during which time he learned to fly. On going up to Brazenose College, Oxford, to read modern languages, he joined the University Air Squadron and showed off his joie de vivre by looping the loop in his Chipmunk aircraft over the college quad. Marrying Jean Stewart in 1953, Thacker needed a job and found one in Cyprus as personal assistant to a Greek millionaire. There were two conditions: that he learned Greek and could type very quickly. His predecessor in the post had been the novelist Lawrence Durrell. moving back to England, Thacker returned to Oxford for a Diploma in Education.

To pursue his doctoral studies, Thacker travelled with his growing family to Indiana university where, in 1963, he wrote his thesis on ‘Attitudes of European Travellers in the Levant (1696–1811)’. This gave no clue to his later interest in garden history, but it did reveal the wide scope he gave his enquiring nature. For the next three years he moved to Trinity College Dublin, where he taught French literature. Following that for fifteen years he taught in the French Department of Reading University, from which he published his Voltaire (1971) and his critical edition of Candide (1968), in addition to frequent contributions to language journals. He would later publish his own translation of Candide (1996).

It was while at Reading that Thacker began to understand the great importance of gardens in European culture. He had the advantage of being able to read much of European literature in the languages in which it had been written. His ‘conversion’ to garden history can be traced through his publications and those to which he contributed. He was a natural choice to be the first editor of Garden History, the journal of the then Garden History Society, a role he undertook between 1972 and 1980. There followed Masters of the Grotto, Joseph and Josiah Lane (1976), The History of Gardens (1979), Of Oxfordshire Gardens (1982), The Wildness Pleases; The Origins of Romanticism (1983), England’s Historic Gardens (1989), Historic Garden Tools (1990), The Genius of Gardening (1994) and Building Towers, Forming Gardens: Landscaping by Hamilton, Hoare and Beckford (2002).

In his first, short, editorial for Garden History, Thacker ended, quoting from William Shakespeare’s The Tempest: ‘There is “much business appertaining”. Let us get on with it.’ And get on with it he did. Leaving Reading University, in 1984 he was appointed the first ‘in-house’ inspector of the Register of Parks and Gardens of Historic Interest, a position he held until 1987. Thacker did not begin with a blank sheet: a great deal had already been done for English Heritage by Peter Goodchild and David Jacques at the University of York, but he did set the course for it as a national Register. He understood that there was more to heritage protection than research and recording. It was also imperative to give the subject a higher public profile. He worked tirelessly with Rosemary Nicholson to establish the Museum of Garden History in 1986, and served for many years as a trustee.

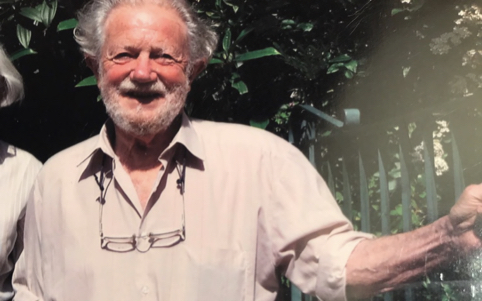

Christopher Thacker, photographed by Hazel le Rougetel, during his editorship of Garden History.

It was as editor of Garden History that Thacker met Thomasina Beck, the authority on embroidery and the influence of flowers in embroidered designs. They met briefly on the steps of the Victoria and Albert Museum to discuss an article she had written on Elizabethan Knot Gardens, which she offered the journal. This duly appeared in the autumn 1974 edition as ‘Gardens in Elizabethan Embroidery’. In due course they married. Deeply in love, it was she who sustained him during the long years in the shadow of the vascular dementia that overtook him in 2004. Although progressively overtaken by confusion, some parts of his character proved indestructible until the end of his days. His love of good wine and good friends and music, his interest in their garden in the beautiful Vale of Wardour, his kindness to strangers and his enduring sense of happiness remained undimmed. On becoming lost in the course of a conversation, he would quietly get up, walk to his piano and play music from memory.

Since the days when Thacker was actively engaged in garden history, there has been a huge body of research that was not then available to him. On occasions he had to endure less-than- favourable reviews, ironically one of which appeared in this journal. In his field he could not claim a greater perfection than many of his contemporaries. His most important contributions were in his encouragement to those who followed him and in widening an understanding of the cultural framework underpinning the making of gardens and landscapes.

The Wildness Pleases is, arguably, his most important book, and one that ranges wider than garden history. It is one he had wanted to write since the early 1960s, but delayed for twenty years until he felt, as he explained in his foreword, he had ‘read enough’. It was republished by Routledge in paperback in early 2018.

In a 2012 occasional paper by Dr Brent Elliott, Librarian of the RHS Lindley Library, The Development and Present State of Garden History, he summed up the value of Thacker’s work:

Much of the approach introduced by the cultural historians has become simply the norm in subsequent history. Christopher Thacker’s History of Gardens (1979) is probably the outstanding example in general garden histories of the late twentieth century: a scholar of French literature by profession, Thacker provided much literary and philosophical background to the development of gardens, but also kept an appreciative eye open for whimsy, and was the first garden historian to include a chapter on water jokes and mazes. Cultural history can be light-hearted.