GT Japan Study Tour 2018: Full of Eastern Promise

Marilyn A Elm

Escaping ‘The Beast from the East’ in late March, we were met by glorious blue skies and warm weather upon our arrival in Kyoto. It was a particularly auspicious time, of course, since the Japanese population were celebrating the centuries old practice Hanami (flower viewing) the main focus being the transitory beauty of the cherry blossom or ‘Sakura’. Prunus serrulata was the common cherry, and the variety ‘Somei Yoshino’ being the most popular, with almost pure white flowers covering the leafless trees in dramatic fashion. There was even the Sakura-zensenor ‘cherry blossom front’ being forecast by the weather bureau, and informing all, of the best time to ‘view’. Many locals were adorned in traditional kimonos, strolling or picnicking under the trees, or along the Philosopher’s Walk, presenting a joyous spectacle that could have come straight out of the Mikado or Madame Butterfly! It was evident throughout the trip, such activity was a continuing testament to the Japanese’ love of nature, and something we explored with our garden visiting, ably led by Kristina Taylor and supported by Mark Rawlins of Inside Japan Tours.

The Japanese garden takes several forms, and has a complex and long history, developed over the centuries by aristocrats, monks and feudal lords. Usually regarded as a high art, it expresses religious and philosophical ideas ranging from Shintoism (Japan’s indigenous religion), and from China, Taoism and Buddhism – very different from the classical roots of Christianity and Islam that have shaped European garden traditions.

Shinto, sees man, animals and plants as equal, and everything has a spirit, even stones, trees and mountains. Shinto practitioners built and dedicated shrines to the supernatural world of the spirits called kami. Red Torii gates (above) are the symbolic entrance to this world, and we saw many of these impressive structures on this trip, the most spectacular being the ‘floating’ Torii Gate 1168 in the bay approaching the forested, mountainous and sacred Miyajima Island and the 6th century Itsukushima Shrine. Taoism emphasises oneness with, and contemplation of nature, and fed into Buddhism which brought meditation. This was introduced into Japan from China via Korea during the Nara period (710–794) and the Heian period (794–1185). Zen Buddhism was not introduced as a separate school in Japan until the 12th century during the later Kamakura period (1185–1333).

Chinese Taoist legends spoke of five mountainous islands inhabited by Eight Immortals who lived in perfect harmony with nature. Each Immortal flew from his mountain home on the back of a crane. The islands themselves were carried in the oceans on the backs of giant sea turtles. The Japanese considered cranes and turtles as symbols of longevity. In Japan, the five islands of the Chinese legend became one island, called Horai-zen, or Mount Horai. Replicas of this legendary mountain, the symbol of a perfect world, are a common feature of a traditional Japanese garden, as are representations of turtles and cranes.

One of the earliest capitals of Japan was Nara, founded in 710 and modelled on a Chinese city (Xian), and known then as Heijo. Many early Buddhist temples were part of the city’s development, especially the Hall of the Great Buddha Todai-ji Temple (752). We walked through the extensive Nara Deer Park, down its central avenue to the imposing Nan-Daimon Gate (1199)(above) and Niostatues which guard the temple. Rebuilt in the 13th century, it shows the influence of China in its’ architecture, a precursor to later Japanese styles. Beyond the gate the impressive Todai-ji Temple stood. Nothing could prepare us for the largest wooden structure in the world, despite it now being only two thirds the size of the original (don’t look at the people in the foreground, but look at those standing under the structure!).

The scale is immense, as is the sitting bronze Buddha on a lotus throne inside. In Buddhism the lotus is associated with purity and spiritual awakening. Considered pure, as it is able to emerge from murky waters perfectly clean, and is a popular plant in Japanese gardens.

Continuing within the Nara region, Kristina took us to the ancient site of the Heijo Palace, now a quiet rural spot. It was abandoned when the Emperor moved his court to Kyoto (Heian-kyo) in 794. Archaeological research and reconstructions have been carried out here, including the east palace garden To-in Teien. It displays the very origins of garden making in Japan, and the basis of the early ‘shinden-style’ garden, developed in the peaceful Heian period by aristocrats devoted to the arts. Their villas and palaces were surrounded by large gardens used for elaborate parties and for recreational activities such as boating and fishing. Designed after Chinese concepts, the gardens featured large ponds and islands connected by arched bridges under which boats could pass. A gravel-covered plaza in front of the building was used for entertainment, while one or more pavilions extended out over the water. Also significant at To-in Teien, is the pebble lined stream, orientated so as to flow in and out of the pond, carrying away all the bad spirits, toward the white tiger.

The choice of Kyoto as the new capital, was apparently due to the auspicious alignment of its’ rivers running from north to south. It was interesting to view the remains of the palace and garden Shinsen-en (‘Sacred Spring Garden’) built by the Emperor when the capital moved there. Located south of Nijo Castle, in the west of Kyoto, the garden has been restored in layout, with a pond at its’ centre. A small island in the pond is reached by a striking vermillion bridge.

However, a structure even more stunning and reputedly Kyoto’s oldest building, was to be found within the large temple complex of the early Heian Daigo-ji Temple, 874. It took the form of an immense five storied pagoda, representing the five elements of Buddhist cosmology, and is one of the few pagodas left.

In the late Heian Period, Pure Land (Jodo) Buddhism gained popularity, promising a ‘rebirth’ in the ‘Western Paradise’ of the Amida Buddha or Pure Land. Consequently, gardens were built to resemble that Buddhist paradise. Similar in design to Shinden Gardens, they featured a middle island (nakajima) in a large pond with lotus flowers, connecting bridges and beautiful pavilion buildings.

We visited a rare example at Byodo-in, in Uji and marveled at the surviving wooden Phoenix Hall 1053; it’s on the back of the ten yen coin. Chinese in style, it has gracefully upswept eaves and two bronze phoenixes on the gables of the main roof. It houses a gilded statue of the Amida Buddha looking to the west. The setting is now a remnant of the ‘pure land’ garden. It is said that members of the family would sit across the pond to the east and look at the seated Buddha, imagining themselves reborn in Amida’s ‘Western Paradise’.

In contrast, we visited the nearby architecturally modern Genji Museum. Here is featured the first ever novel Tales of Genji, 1005, written by a lady in waiting Murasaki Shikibu, and including descriptions of the aristocratic gardens at this time. Also displayed was an interesting model of a domestic villa with a Pure Land garden.

The gardens of the Kamakura and Muromachi Periods (1185–1573) are perhaps the most well known, and we were fortunate in visiting some of the most iconic. At this time a shift of power from the aristocratic court to the military elite was completed. The Emperors ruled in name only; real power was held by a military governor, the shogun governing his shogunate.Relations were re-opened with China, and Chinese monks brought with them a new form of Buddhism called Zen or ‘meditation’. The doctrine was adopted by the warrior nobles the samurai, and helped shape their standards of conduct.

Zen Buddhism, however, had a significant influence on gardens attached to temples. Some of the earliest were created by the Buddhist monk Muso Soseki, at five major monasteries in Kyoto. We visited the beautiful surviving gardens at Tenryuji-in Temple, 1339, in the north-west of Kyoto, where he served as the first head priest. An important shrine in the picturesque Arashiyama area, it features a central pond surrounded by rocks, trees and the Arashiyama mountains, and is the oldest surviving example of using shakkei or ‘borrowed view’ of the scenery beyond its boundaries. The garden was really at the beginning of a new era of garden making, and forms a transition from the Chinese style to an independent Japanese form.

The Kare-san-suior ‘dry landscape garden’ associated with many temples at this time, is a particular response to the coming of Zen. A miniature stylized landscape, it uses pruned shrubs and trees, moss, and in particular, carefully composed arrangements of rocks as mountains, and sand or gravel representing the ocean or flowing water, and raked to give the pattern of waves (samon).Their purpose was to facilitate meditation, and they are meant to be viewed while seated on the porch of the residence of the hōjō, the abbot of the monastery. It is these gardens, of course, which perhaps epitomize the most appealing characteristics of Japanese aesthetics that we recognize in the West: simplicity, elegance and restraint.

We visited the famous example at Ryoan-ji, Kyoto, 1499, on the south side of the abbot’s house, and referred to as ‘a sermon in stone’. It visibly embodies many tenets of Zen belief through symbolism and aesthetic expression. Enclosed by earthen walls and small in size, it still expresses infinite space. The important Zen element of empty space or mu,heightens our appreciation of the composition. In a sea of raked white sand, fifteen stones each within a tiny island of moss are arranged in groups of 5-2-3-2-3 and only fourteen of them are visible from any one point. This reflects the Buddhist belief that the number fifteen denoted completeness, a perfection that is difficult to achieve in this world.

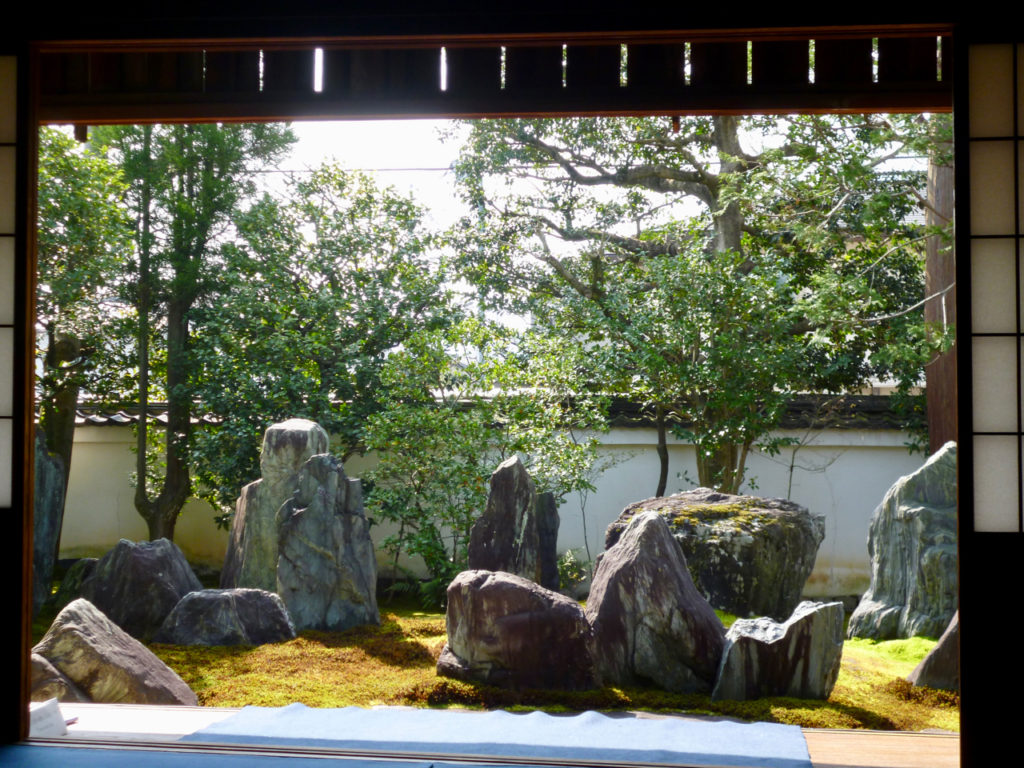

Another temple garden of extreme significance was found at the delightful, high ranking sub-temple of Daisen-in; part of the important Daitoku-ji temple complex in Kyoto, 1509. The main hall is one of few which survived a fire, and is the oldest remaining example of the Hoji style of Zen Buddhist architecture. Inside there were exquisite painted screens. It has small connecting gardens which surround the hall, telling the metaphorical story of the journey through life. They employ all the elements of a classic Song dynasty Chinese landscape painting. A dry river flows from a series of upright rocks, Mt. Horai, east and west through a miniaturised landscape, of beautiful scaled trees, shrubs and pebbles, past turtle and crane islands and ‘boat stone’, to its journey’s end – the sea – in the south garden, a sand landscape with two perfectly formed sand cones, and a single tree. It was beautifully maintained.

Other contemporary gardens reflected influences from Chinese artists and poets. Kinkaku-ji ‘The Golden Pavilion’ designated as a National Special Historic Site is such an example. Its stunning gold façade reflecting in the ‘mirror pond’ didn’t disappoint, and its setting, using the woods behind, and the borrowed views of the mountains, was magnificent.

Also visited was its counterpart Ginkaku-ji ‘The Silver Pavilion’, 1482, (never covered in silver) built on the side of the hill. The gardens were an unusual combination of a Zen and early ‘strolling’ garden. Our initial approach brought us to a raised bed of white sand known as the Silver Sand Sea in which there is a stunning truncated sand cone called the Moon Facing Height or Moon observing platform (possibly even Mount Fuji). The surrounding garden offered a beautiful woodland walk.

Here, the ground was covered in moss, and was being swept clean by a gardener. Apparently, there are 2,500 named varieties of moss in Japan, its humid climate offering perfect conditions for the plant to thrive. Another Japanese concept called Wabi-sabi may play a key role in moss’s popularity. It is an aesthetic that values qualities as impermanence, humility, asymmetry and imperfection, and moss grows seemingly at random, in asymmetrical patterns. It is also symbolic in Buddhism. On our trip we saw precious moss for sale in neat wooden boxes.

Another typical Japanese garden element we encountered on our travels was the Tea House Cha sitsu. The custom of drinking tea, first for medicinal and then also for pleasurable reasons, had been widespread throughout China. Introduced by Buddhist monks to Japan, they used it as a stimulant to keep awake during long periods of meditation. However, tea drinking chado,the way of tea, was encouraged to prolong life and promote a healthy constitution, and by 16th century was elevated to a way of truth. This led to the Japanese tea ceremony cha-no-yu, designed to clear the spirit and mind in readiness to accept spiritual and aesthetic values of nature and simple rusticity ie ‘sabi ‘and ‘wabi’ principles. The tea used is a frothed up powdered bright green tea matcha – an acquired taste some would say!

The ceremony took place in rustic, often thatched tea houses which were small wooden structures with just enough room for two or four tatami mats. Many we saw were incorporated as decorative features in the larger gardens, but traditionally would sit within a smaller Tea Garden Cha niwa approached by a pathway, the roji meaning ‘dewy ground’ with the association of dampness, shade, moss and stones. Planting is kept simple, and usually without much distracting colour. A stone water basin (tsukubai) initially used for ritual cleansing, is placed outside the teahouse for use before entering, and usually fed by a bamboo pipe kakei. A wooden ladle is provided if for drinking. It should be said that the iconic stone lanterns are typical elements of such a garden, having originally only been at Buddhist temples or Shinto shrines.

Several gardens visited were ‘stroll’ gardens with ever changing views, developed initially in the Edo Period (1603–1867) for the entertainment of the feudal lords who owned them. Such gardens had ponds, islands, arrangements of rocks, beautifully pruned trees and shrubs, artificial hills, winding paths, and many included shrines and tea houses just for interest and decoration. ‘Hide and reveal’ miegakure, and borrowed views shakkei, were important devices. Often famous views would be created either real or literary such as Mount Fuji, or a theme may be included such as a rice field to represent rural life.

As example, the Isuien Garden (1603–1867) in Nara, belonging to a middle class merchant, has a miniature stroll garden, with a rocky shoreline and turtle and crane island, and displayed many of the techniques of the larger more important gardens. It uses shakkei wonderfully, bringing in the views of the Nandaimon Gate and the surrounding Nara mountains.

Another, the Shukkeien ‘shrunken scenery’ Garden, 1620 in Hiroshima, has been delightfully restored after the bomb. It is a Daimyo stroll garden of ten acres and is built around a central pond with small islands and miniature trees, so that looking across the pond, the whole appears much bigger and grander. The stone moon bridge (Chinese style – in the background here) was built in 1780. The garden displayed many traditional and familiar features.

Of note, was evidence of pine needle thinning, for either aesthetic or practical purposes. This Niwaki, is the ancient art of Japanese pruning, sometimes to create dense tree foliage, or to lighten it where necessary, or to shape it for desired effect. The true form of ‘cloud’ topiary and other clipped forms were evident on our travels, particularly as part of the more modest urban gardens or Tsuboniwa, where they were stuffed into tight spaces around the home. This is probably not surprising, when about 73% of Japan is forested, mountainous, and unsuitable for agricultural, industrial, or residential use. As a result, the habitable zones, mainly located in coastal areas, have extremely high population densities. Following the horticultural theme, we noticed also older trees on ‘crutches’ to keep them from breaking under the weight of snow.

Probably one of the classic examples of the Edo stroll garden was the Korakuen Garden, 1686/7, in Okayama. It was built by a local daimyo, who would have entered the garden by being rowed across the river from the castle (which can be seen in the distance). Damaged after flood and World War II, it has been restored based on Edo period wood block prints and paintings. It is now an extensive public park with several elements, including orchards, a tea plantation, tea house and a zig-zag bridge over iris planted streams. NB. Photographs in Josiah Conder’s book from 100 years ago, show little change in both the Korakuen and Shukkeien gardens, evidence of successful restorations.

Exploring the traditional gardens, and becoming familiar with their history and development was fascinating, but even more so when faced with more modern interpretations by Japanese designers.

Shigemori Mirei (1896–1975) was the most important 20th-century garden historian and designer in Japan. He is noted for studying and publishing his historical survey of 250 Japanese gardens in 1936 as “The Illustrated History of Japanese Gardens,”Nihon Teinenshi Zukan. He began practicing as a garden designer in 1914. He was greatly influenced by Western culture. The modernist movement which arrived in Japan during the 1920s and 1930s had a profound impact on his approach to design. He frequently used the term “eternal modern” to represent his ideas, and to define the aesthetic sense that qualifies much of his work. The expression, he explained, referred to his concept of the balancing of beauty; a parity between the classical and contemporary.

We visited the Shigemori Garden and Museum which was the house he bought in 1943, and where he lived and died. It is a traditional Japanese machiya (town house) built 1789. We were met by his grandson Mitsuaki. The garden was exquisite! Small in extent, it consists of four blue rock configurations symbolizing the Elysian islands: Hojo, Eiju, Horai and Koryo placed on the sand garden. Horai island consists of a crane style rock composite and Hojo, a tortoise style rock composite. There are biomorphic forms too, described in carefully tendered moss. For those who went on the GHS Brazil study trip in 2009, very reminiscent of Burle Marx designs. The garden is surrounded by trees and over-looked by a veranda and sparse main room with shoji screen, tatami mats and a hanging paper light designed specially by his friend Isamu Noguchi. The tea ceremony pavilion was a rich hybrid of traditional and modern design.

Shigemori’s first major work was a design for the garden at Tofuku-ji Temple in 1939. He designed 240 gardens, and worked mostly in Kare-san-sui or dry landscape gardens. Many of his gardens are on existing religious sites, but a few of his works are in cultural or commercial settings.

Tofukuji Temple, isone of Kyoto’s UNESCO-designated World Heritage sites. It is the headquarters of the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism founded in 1236. There was little money at the time, and Shigemori saw an opportunity for recycling, in his creation of the four gardens around the hojo which we came to see. The south garden has rocks representing the islands of the immortals and moss covered mounds all placed on raked white sand. The East gardenis composed of moss, raked gravel and seven round granite stone pillars representing the ‘Great Dipper’ constellation.

The West Garden has clipped azaleas in squares and ‘Burle Marx’ curves, and the often photographed North Garden is a modern, innovative style moss garden, with square stones set at irregular intervals.

Some of Shigemori’s arresting work is carried out at Matsuo Taisha, 701, founded by a Hata clan immigrant from Korea, bringing sake brewing techniques. The Shinto shrine has long been associated with sake brewers, and donated sake barrels are put on display. We saw such displays several times on our trip. Sipping a cup of sake is still regarded as a prayerful act of symbolic unification with the gods.

The Koyokusui Garden or ‘Undulating Stream Garden’ at the temple, is a stunning, mainly hard landscape, based on the Japanese tradition of setting dolls a float on boats that symbolically carry away evil spirits. The curving stream Shigemori constructed, is also reminiscent of aristocrats’ gardens of the Heian Period, where partying courtiers would enjoy a literary game in which one would write the first line of a poem and then float it down a meandering waterway to another guest, who would add a line. Kristina floated some folded paper as demonstration. The stream is unusual for Shigemori, in that he rarely used actual water in his gardens, preferring the abstraction of white gravel or sand, and also exceptional in being made of concrete. The banks are embedded with flat blue stones; the stream bed with gravel. There are no trees in the garden, but a contiguous bank of azaleas, clipped into the form of a turtle, a symbol of longevity.

The Iwakura Garden or ‘Garden of Ancient Times’ has stone settings tilted at exaggerated angles; a powerful arrangement, standing in a bed of bamboo grass for the Shinto gods to come and visit. Shigemori died a few months after he completed it.

His Horai Garden representing the ancient Chinese Realm of the Immortals in the Kamakura style, is the first landscape visitors see as they approach the shrine’s main building. Shigemori designed this garden with water and dramatic rock formations, but his death in 1975 obliged his elder son to complete its construction.

The tour took us to Hiroshima, and the Peace Memorial Park and Museum, on perhaps a fitting rainy day. A sobering experience, viewing the skeletal ruins of the A-Bomb Dome, and the saddle shaped Cenotaph aligned to frame both it, and the Peace Flame. Particularly poignant, was the Children’s Peace Monument in the form of a girl with outstretched arms with a folding paper crane above. The girl, who died from radiation, believed that if she folded 1,000 paper cranes she would be cured. To this day, people from around the world offer folded cranes which are placed in a cabinet nearby.

We finished our tour at the white egret castle and gardens at Himeji, 1601, a striking contrast to the innovative and modern Miho Museum, designed by I. M. Pei where we had started; but that’s Japan. From traditional bento boxes to the Shinkansen (Bullet Train), a profound experience in every way.